I would like to turn now to what may be the most fundamental aspect of the Andean Cosmovision, ‘ayni‘. Ayni is the principle of reciprocity. The essence of ayni is that when you receive something you give something back in return. This keeps balance in the relationship, but it also does more than that, it nourishes the relationship as well.

Ayni informs the Andean people’s relationships with each other, and in that context it can be easily understood. It is when the Andean people apply ayni to their relationship with Nature and the Cosmos that we move into mysterious territory and begin to glimpse the profound beauty of their Cosmovision. To understand how ayni works in this context we first need to understand their very different view of Nature and the Cosmos. It is not possible to have a true relationship with inert, mindless, matter, and in the Western view of reality that is how rivers, and stones, and trees, and the Cosmos itself are basically seen. We can love a forest, or the Earth, but within our world view it is hard to conceive of them loving us back. The Andean people have a very different experience of reality, one that allows true relationships with Nature and the Cosmos. This was covered in the earlier post Andean Cosmovision: The Basics and I recommend that if you haven’t already that you read it and the post Barefoot in the Mountains before proceeding so that you will be better able to understand what I am going to say about ayni.

Village men threshing wheat.

Let us begin by looking at ayni in the context of the Andean people and their relationships with each other. Ayni shows up clearly in the work that the people in a village perform together. When it is time to work a family’s field the men and women in the community unite to work it as a community. The sowing of a field, for example, involves a line of men working foot plows to overturn the soil, followed by a line of women who plant the seeds. When such communal work is done the recipients rarely express thanks, for it is just part of life that they will then establish balance by working their neighbor’s fields in turn. When you give you receive, and when you receive you give, balance is maintained, both sides are nourished, and the community is healthy.

Reciprocity is like a pump at the heart of Andean life. The constant give-and-take of ayni…maintains a flow of energy throughout the ayllu [community]. Allen, 2002, pg 73.

I would like to share some of my own experiences with ayni, from the perspective of a Westerner entering into a relationship with the Andean people. My trips to Peru involve working with various paqos and healers, and this ‘working with’ often involves my participation in the ceremonies and healing rituals that they provide. What I can give them in return to balance our relationship, what they really need that I have, is money.

At the beginning of my exploration of the Andean Cosmovision I felt uncomfortable about giving money in reciprocity. From my Western perspective it just didn’t seem quite right to give money for a sacred experience. There is a lot of cultural background to those feelings, tied to our views about the relationship between the sacred and the secular and how– when the two are mixed in the wrong way–the sacred becomes profane. Ayni, however, is not the same thing as payment. Ayni brings people closer together, the goal is balance rather than gain, mutual support rather than advantage. When I was able to shift from my culture’s Cosmovision to the Andean Cosmovision I was able to enter into the true ayni of the relationship. On their side they were willing to do the same, to interact with me in ayni within the context of the ceremony, rather than slipping into the Western capitalistic relationship that is encroaching into their culture. It is interesting that when the ceremony is over, and ayni has been completed by my giving them money, then the context usually does shift, the sense of the sacred evaporates, they pull out their goods-for-sale, and some hard haggling begins. The two ways of being in relationship, one of ayni within the context of the sacred, and one within the context of selling, could not be more different.

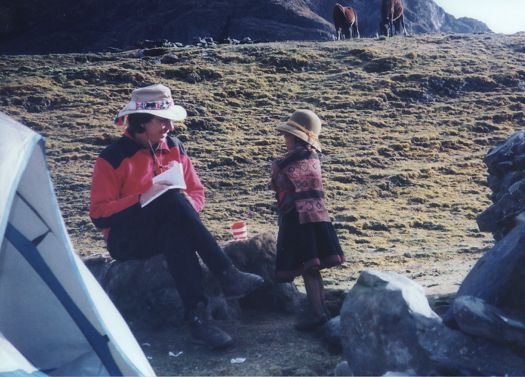

I would now like to share another context where I experienced how ayni works in Peru. This specific instance occurred in one of my more recent trips. I had brought along some extra money to give to the people of the Andes, not much, but it doesn’t take much to really help out someone who lives in the high Andes. The challenge was to find a context where the money could be given in ayni, for it is so easy for it to shift into a context of “the (comparatively) rich Westerner giving money to the poor and needy indigenous person” which is not ayni at all.

I was able to proceed with the help of an Andean friend (who is a genius at getting around my misled but well-intentioned efforts and helping me to do something even more beautiful than I anticipated). In this case we were in a very small village high in the Andes, which was probably important as there the people still lived a life governed by ayni. The following story is perhaps the best way I can share how ayni works.

Club of Mothers

I was introduced to several people whom my friend knew could use some help. First I was introduced to a middle-aged man who was suffering from severe diarrhea, he asked if I had anything to help. Being the well-prepared gringo that I am of course I had some medication that is good for diarrhea, and I gave him some with instructions on how to take it. He thanked me most sincerely, and a few minutes later he returned to give me three eggs from his hens, which of course I thought was pretty nice of him. Then I was introduced to two young girls who were orphans and needed some money to get school supplies (in the small villages there are few resources for people who are outside of any family). They smiled and looked shy. I gave them some money and with big smiles they each gave me a hug, then one ran out and returned with a belt she had made to give to me as a present. The village Club of Mothers (who meet weekly to pursue activities for the benefit of the children in the village) gave me a live chicken in ayni for my support. I contemplated texting my sons that I was bringing them home a sister but we ate the chicken that night instead. And at the end of the day I was introduced to a very old woman whose family were all gone and I gave her the rest of what I had. She gently grasped my hand with both of hers and looked into my eyes with a gentle smile and said something to me in Quechua, which my friend translated for me. She said that she had nothing she could give me, so she would pray for me instead. It was a beautiful day.

While ayni in the relationships among humans may be easy for us to understand from our own cultural perspective, when we look at the Andean people’s ayni with the animals upon which they depend then we start to move into territory that is both different and beautiful. I would like to talk about the relationship between the Andean people and their traditional domesticated animals, specifically alpacas and llamas. The following description pertains to people who live in isolated villages in the high Andes, at or above the tree line, and who still live the Andean Cosmovision. These people, and their animals, and their plants, eek out a living at altitudes as high as 15,000 feet, in villages that may be a good two-day walk from the nearest road.

The alpacas and llamas make it possible for the Andeans to live at such altitudes. Unlike other ruminants, alpacas and llamas can graze upon the sparse, high-altitude, grass without damaging it . Llamas carry loads to and from the fields, and from one village to another. They can carry 70 – 90 pound packs, up to 16 miles a day. The hides and wool from both llamas and alpacas are used for clothing. Wool from the alpacas is sold in market towns to obtain sugar, and flour and other materials that cannot be produced in the village. When an animal is slaughtered or offered in a sacrifice every part of the animal is either consumed or used to make things. Dung from the animals fertilize the high-altitude fields or when dried can be used as fuel (it is not a very hot fuel, one time we decided to make hot chocolate at 17,000 feet and it took over an hour for the water to get kind of warm).

The Andean people recognize that their alpacas and llamas cannot survive without human protection, and they equally recognize that humans cannot survive without the alpacas and llamas. The people and their animals share the same resources, and the same weather, and the same hardships of life at high altitudes. The llamas and alpacas are not seen as resources to be managed, they are seen as partners in a mutually supportive dance of reciprocity among beings.

The llamas and alpacas are treated with love and respect, an Andean herder knows every llama and alpaca by sight and all are given names. The llamas and alpacas participate–adorned–in sacred ceremonies, so that the ceremonies may make them happy too. They join the people in appealing to Nature and the Cosmos in times of need. Special ceremonies are held in honor of the llamas and alpacas. In the llama ch’allay ceremony, for example, the llamas are given chicha (locally brewed corn beer) to thank them for all of their work in carrying the harvests up the mountain. During the ceremony a small bell is rung near the llama’s ear to clean its energy.

When an alpaca or llama is sacrificed or slaughtered the event calls for a special ritual. The animal’s feet are tied together and it is laid upon the ground with it’s head in a person’s lap. The person sings to the animal and strokes its head and gently feeds it coca leaves. At the appropriate moment the animal is killed swiftly, and as it dies its feet are untied so that its spirit may begin its run to the sacred mountain Apu Asungate, accompanied by prayers by the people that Asungate may receive the spirit and send it back to be born again in the same corral. Through its death the animal’s spirit is a gift to the Apu who returns the spirit back to the herd in ayni.

As the life force [of the animal] flows towards the mountains and back in perfect reciprocity, the cosmic balance is maintained. (Bolin, 1998, pg 56).

Bounty from the Pachamama and her daughters

Now we will take a step yet further away from the Western view of reality to consider ayni in the relationship of humans with the Cosmos when it comes to raising crops. As the Pachamama (the great mother who is the planet Earth) is but a part of the conscious Cosmos yet has her own consciousness, and the Apus (majestic mountain peaks) are but part of the Pachamama yet have their own consciousness, the chakras (fields in which crops are grown) are daughters of the Pachamama and have their own consciousness as well. Each chakra is responsible for the crop that is grown upon her, and each chakra has a name given by the people who work that field. Before entering a chakra to work a brief ritual of gratitude and respect is given to the Pachamama and her daughter. A little chicha (corn beer) may be poured upon the ground to slake their thirsts. Upon leaving the field another brief ritual may given to thank them for their generosity, in this way ayni is nourished. At that time a little thanks may also be given to Illapa, the god of thunder, thanking him for sending the rain (and for not sending lightning).

Patchwork quilt on the lap of the Pachamama

On one of my trips to Peru we stopped to watch the people gather a harvest of potatoes. It was in the high Andes, on the land between Cusco and the Sacred Valley. The numerous plots were all small, and at different stages of ripeness and containing various crops. The ground stretching up to the mountains looked like a patchwork quilt upon the lap of the Pachamama. Thin trails of smoke rose from a dozen small camp fires scattered across the land. The fires were tended by young mothers and older women. The first potatoes taken out of the ground in the morning had been placed back into holes dug in the Pachamama, covered with earth, and then a fire was lit above them, cooking the potatoes for a meal later in the day. The custom is both practical and sacred, honoring the Pachamama, nourishing her children, and maintaining the relationship between the earth and those that live off of her bounty.

After appreciating this sight, we piled back into our van to continue on our way. As we pulled out my gaze fell upon a young woman tending a fire near the road, perhaps 20 yards away. She looked to be in her early twenties. She was wearing the traditional full skirt and sweater of the Andes made of a woven fabric dyed in colorful shades of green and brown, and a tan hat with a rounded top and a wide flat brim. She was sitting on the ground, in contact with the Pachamama, and nursing her child. As the van pulled away she looked up and for a moment our eyes met, and she smiled. It was the most beautiful smile I have ever seen, a smile that conveyed an absolute contentment with life-at-that-moment, a smile from the heart of the Pachamama.

In the Andean Cosmovision humans are not distinct from Nature, nor is Nature distinct from the Cosmos. The role of humans is not to use Nature for our own good, nor to serve as stewards over it, but instead to interact with Nature in a dance of respect and mutual support. We are but part of the fabric of life, not its apex; children of the Pachamama, but not her special children. Is it any wonder that the fields that the Andeans have cultivated for thousands of years feel as wild and natural as our National Parks?

In the Andes ayni goes beyond the people’s relationships with each other, and with animals, and with fields, to inform their relationships with the Cosmos. When the Andeans gather together socially, or in ceremony, or to do communal work, they perform brief ceremonies to invite into their circle the Pachamama and the Apus and other great Beings of the Cosmos, to honor them and to express respect and gratitude. In their sacred ceremonies, the Andean people offer gifts to the Pachamama, to the Apus, and to the various other Beings of Nature and the Cosmos. This is all done as ayni, to nourish a relationship of mutual support, of mutual service. They serve the Cosmos and the Cosmos serves them, and from this their sense of relationship becomes stronger.

Inge Bolin (1998) summarizes a night of ceremony among the Andeans as follows:

These ancient rites reconfirm a close interdependence among humans, animals, and nature. This night, through a dialog with gods and spirits, we entered the realms of the sacred. We wove threads which symbolically bound us to our physical, social, and spiritual worlds. We reinforced ties with the past, with the Apus, with those ancestral spirits living in mountain peaks, and we looked toward the future, hoping for the aid and compassion of the deities from whom we requested health, prosperity, and peaceful coexistence. We engaged in reciprocity, the hallmark of Andean life; we were offering and asking, giving and taking.

Every gesture and movement was performed with great dignity and elegance. Every ritual carried an expression of respect for others—for gods, humans, animals, plants, and the spirit world. On this night and in the days to follow, the message of the rituals is clear. Only where there is respect can we find a way to live and act together. We must adjust and readjust to accommodate the various benevolent and malevolent forces within the cosmos. Pachamama, the giver of life, is also responsible for earthquakes and other disasters. The Apus are protectors of the herds, but they also send malevolent winds which can bring disease and death. There is no trace of aggression or hostility, domination, or subjugation in any of the rituals. Our offerings, our thoughts, our efforts in dedicating this night to a spiritual dialog among humans, animals, and the powers of nature are meant to reinforce the positive,, to give hope to a life so harmonic and serene, yet so vulnerable in this marginal environment. (pg 43)

This I believe is the heart of the Andean Cosmovision. Ayni is the pump that sends the energy flowing through the people and their Cosmos. There is a mistake, I think, in our culture to remove the Andean meditations from their context, to see them only as a technology for personal transformation. The meditations, however, are fundamentally about our relationship with Nature and the Cosmos. The benefits of the meditations come from this relationship, and being a relationship we need to attend to our side of the relationship as well, with love and mutual support and respect.

There is one level of ayni I have not talked about yet that I would like to mention. The Andean people are willing to share their Cosmovision with the West and many of us feel that we have benefited greatly by their willingness to do so. For the circle of ayni to be completed, so that not only balance is achieved but that both sides may be nourished by the exchange, we need to give back to the Andean people, particularly those who have given this gift to us. I recommend that if you pursue more knowledge about the Andean approach from various authors and workshop presenters that you look to see if any of the money you give them goes back to the Andean people.

If you find this Salka Wind web site to be of value to you and would like to donate some money as ayni you can do so at the Donate page. This nourishes my efforts in this work and leaves me feeling like we are on this path together and that this project is the best thing since puffed rice. I always give a goodly chunk of any money I receive from my Salka Wind work to the Andean people to insure there is ayni at that level as well. If you would like to give some money to nonprofit organizations that work to benefit the Andean people–in a way that is guided with wisdom so that their lives and their culture are nourished rather than damaged–you will find links in the Resources page of this web site, there are undoubtably other good nonprofit organizations working to help the Andean people out there as well.

Note there is a subsequent post on ayni called ‘Ayni Revisited‘.

This post on ayni draws heavily from the work (cited and uncited) of Inge Bolin. I strongly recommend her beautiful book Rituals of Respect: The Secret of Survival in the High Peruvian Andes. I would also like to thank Monique Duphily whose dissertation-in-process on the topic of ayni also contributed to the writing of this post.

Share...