Salka is like a wind that blows through consensus reality from beyond, bringing us into contact with the great mystery and beauty of existence.

‘Salka’ is a Quechua word (the language of the Andes) for ‘natural’ or ‘not domesticated’ energy. The wolf, for example, is more salka than the dog, the condor is more salka than the chicken, and the deer is more salka than the sheep. Salka is the natural energy of all life, it is not quite accurate to say that some beings are more salka than others, it might be better to say that some are more domesticated than others. Domestication is like a veneer through which the light of salka shines through.

People in my culture, including myself, are very domesticated. Much of our attention, energy, and activities are shaped by the social/industrial/technological environment that our society has created. What time I get up, what clothes I put on, how I make a living, what I do for entertainment, are all organized around the rules and options provided by our society. Even more important than the domestication of our time and energy, however, is the domestication of our understanding of who we are as beings in this Cosmos.

The very concept of ‘who we are as beings in this Cosmos’ may seem strange as many of us think about ourselves in terms of our roles in our society, or in our family, or in our place of work. Our ideas of ‘self’ tend to be very domesticated. My society has ideas about what it means to be human (drawn largely from science or religion), what it means to be male (drawn largely from Madison Avenue), what it means to be a professor, a father, a husband, and so on. There are some options supported within those roles, and there is always the possibility for rebellion, but even then my thoughts about myself are largely in relationship to what my society proscribes.

Being a domesticated human is great, it opens the door to all of the comforts and opportunities that our society can provide. There are, however, two major drawbacks to this domestication. One drawback is that our society has created an environment where what it takes to survive in a city or thrive in a business involves behaviors that are killing our planet, and this is accompanied by incentives to downplay or hide this consequence. The second drawback to domestication within our society is that it only recognizes and supports part of the totality of who we are. In modern society who we are is mainly a ‘consumer’ and we (at least in the U.S.) are bombarded with thousands of messages a day designed to reinforce that aspect of our existence. The good news is that we are vastly more mysterious beings than our society would have us believe.

Salka is also part of our heritage as beings on this planet. There are people in the high Andes who are very salka. Imagine being a young child living at 15,000 feet in a tiny settlement in the Andes. You live in your family’s small stone house, built of the material of the Pachamama, such a house is known as a ‘wasi-tira’ (literally a ‘house of the Earth’). The heart of the house is the q’uncha, an oven made of earth, a hardened hollow dome of adobe that has a opening on the side for feeding wood into the fire and a few openings on top that are just the right size to sit the pots. You awake in the morning to the warmth of the q’uncha and the aroma of the soup that your mother is cooking for the family. Climbing out from under the llama skins you prepare to take your family’s alpacas up the mountain to feed. You take along your warak’a, a woven sling that you use to throw rocks to the side of the herd to direct them where you want them to go and as protection from the pumas, the condors, and the foxes of the high Andes. As the sun licks the frost off the ground you slowly lead the herd up the mountain, to perhaps 16,000 feet, where there is ichu grass upon which they can feed. You find a comfortable place to sit. A thousand feet below is your home, a little smoke coming out of the hole in the roof. But up here it is all wild. Despite your being at 16,000 feet the Andean peaks tower high above you. All you hear is the soft steps of the alpacas as they graze, and the wind coming down from the mountains. The air is clear and the towering peaks, although they are miles away, seem almost close enough to touch. Below you a condor glides down the valley, barely moving its wing tips to control its flight. You notice clouds gathering around the Apus, perhaps the Apus will send rain in your direction, or even the deadly thunder and lightening. And you know that the Apus are as aware of you as you sit there as you are of them. This is salka, you are surrounded by salka, and you are salka too.

As much as it can be defined in words salka is the essence of who we are, our domesticated self is built on top of that as we mature in our culture. To reach the full expression of being human we need to know both, it just happens to be that in our culture the emphasis is overwhelmingly toward our domesticated self. The Andean meditations help us get in touch with the salka aspect of our being.

Salka is beyond definition, beyond comprehension, it is vastly mysterious, and tied somehow to innate beauty. As we are, in essence, salka the same can be said of us. I suspect that the nature of great art is that it provides a path for salka to emerge into our domesticated life. We don’t need to be skilled at drawing, or music, or poetry to express salka. “My suggestion is that you make your life a work of art.” (Americo Yabar)

Epilog One: Some friends and I were bumping along a dirt road through the Andes in a minivan. The Beatles are rather big in Peru and the driver had put on a cd that could be described as ‘101 Pan Pipes do the Beatles’. We were all singing ‘With a Little Help from My Friends’ as we passed through a small village in the mountains. What struck me suddenly, very deeply, was that the Beatles were an expression of something, some way of being in the world, of some way the world could be, and that somehow, despite its surface appearance and its poverty, the village I was looking at was the world the Beatles were singing about.

Later I read a story about the anthropologist Gregory Bateson (1904-1980). A student asked him what the purpose of art was. He replied that the purpose of art was to make life seem worth living. The student then asked him if he knew of any contemporary artists who had actually pulled that off. After a long pause, he replied ‘The Beatles’.

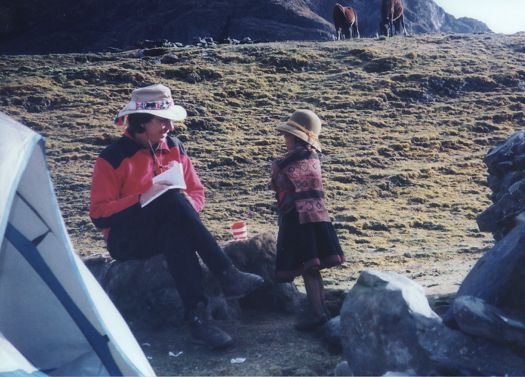

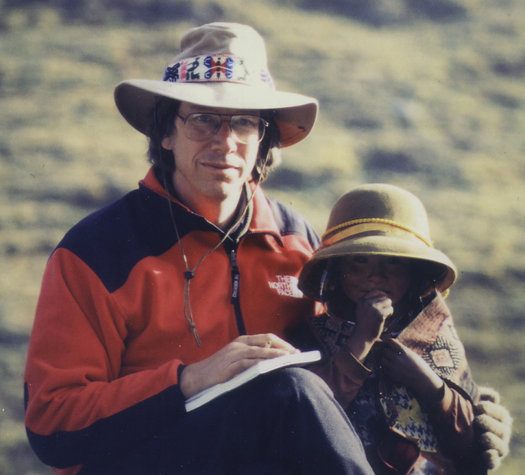

Epilog Two: On one of my trips to Peru we traveled to a very salka village high in the Andes. To get there we had to drive for six hours on a dirt road from Cusco and then get on horses and travel for two days through the mountains, going over two 17,000 passes. The village itself was at 15,000 feet. We set up camp on the other side of a hill from the village. The next morning I got up and had a cup of coffee and sat on a stone watching the sun rise. I began to write in my journal. Looking up I was surprised to see a small girl staring at me from a few feet away. She was very salka, and she had come from the village to check us out. There began one of the most touching moments of my life, and my friend just happened to lean out of her tent and take our picture.

I didn’t speak Quechua and she of course didn’t speak English. But I have been the father of young children and I know how to communicate without the necessity that the words be understood. I touched her necklace and told her how pretty it was, I said other nice things to her with an open heart, and then she settled down with me and together we watched the day slowly begin to unfold.

Share...

August 14, 2011 at 2:22 am

You reminded me of my own Salka. Thank you.

August 14, 2011 at 11:10 am

So appreciate your way with words, your clarity-Oakley! I recently received guidance that the Wolf is my guide right now, my totem. Makes such sense as I am living and moving in more salka ways…remember our trip to the ocean there in Peru…still intending to get back to the Andes one day. Muchas gracias, waiki.

August 18, 2011 at 5:48 pm

Hi, Oakley.

Yours are the posts I most look forward to reading. I love the beautiful simplicity of the Andean cosmovision, expressed in your words … I invariably finish with a lump in my throat – and a feeling of longing reaching into and out of my heart.

I’ve met and worked/played with don Americo a few times here in the UK, but it sure feels like a long time between visits. Your site, your words and the sentiments you express help to bridge the gap.

Gracias, Waiki,

Robert

August 19, 2011 at 8:21 am

Thanks Robert.

February 26, 2024 at 10:05 pm

13 thank yous, honey in the heart

making my way through your posts, joy with every word, tears with this one

almost 13 yrs since these were written, like finding lost treasure

as I write the honey of my heart is in Arequipa, mourning the passing of her mother

gracias, long life, peace

February 27, 2024 at 7:35 am

Thank you for sharing your heart-felt words. Tears of joy and sorrow.